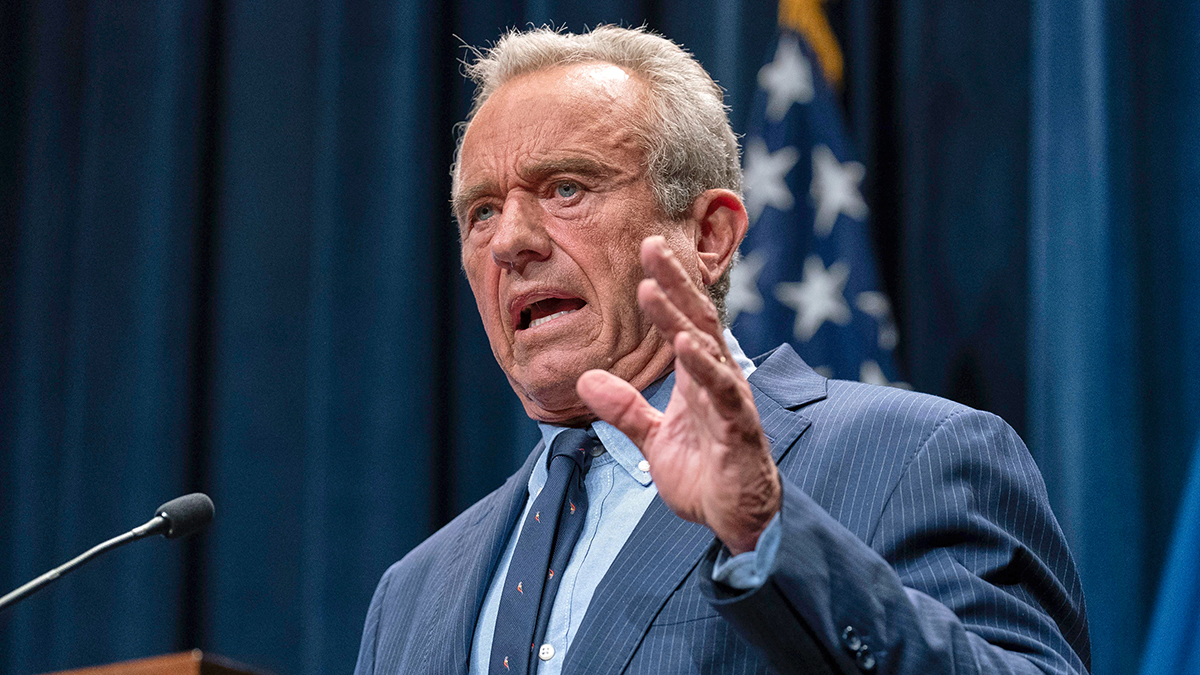

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. ousted all 17 members of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine advisory panel, claiming it “has been plagued with persistent conflicts of interest and has become little more than a rubber stamp for any vaccine.” But there’s no evidence of problematic conflicts of interest or that the group inadequately scrutinizes vaccines.

Kennedy announced the removals in a June 9 Wall Street Journal commentary. In a press release from the same day, Kennedy said that the move was necessary to restore public trust in vaccines. “A clean sweep is necessary to reestablish public confidence in vaccine science,” he said. “The Committee will no longer function as a rubber stamp for industry profit-taking agendas.”

Stream Connecticut News for free, 24/7, wherever you are.

The few examples of conflicts of interest that Kennedy provided are either misconstrued or many decades old.

“Allegations of conflicts of interest have no basis in fact,” Dr. Tom Frieden, a former CDC director, said in a video posted to X the day after the announcement.

Get top local Connecticut stories delivered to you every morning with the News Headlines newsletter.

Dr. Tina Tan, the president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, also called the allegations about the advisory panel’s integrity “completely unfounded” in a statement.

“Wholesale dismissal of the committee is unprecedented, and without justification,” Dorit Reiss, a vaccine law expert at University of California Law San Francisco, told us.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, as it’s formally known, is a panel of independent medical and public health professionals with expertise in vaccines that provides guidance on who should get which vaccines, how often and when. Its recommendations are highly influential and determine which vaccines are free to low-income children via the Vaccines for Children program and which vaccines most insurance companies must cover for no additional charge.

Kennedy’s dismissal of the entire panel follows two major policy changes at HHS that work to limit access to COVID-19 vaccines. In both cases, Kennedy circumvented the advisory panels that normally would have weighed in on such issues. Around the same time as the ouster of ACIP members, HHS also removed the career CDC officials that vet potential members and help plan and organize the meetings, according to reporting by CBS News.

On June 11, Kennedy, who is a longtime anti-vaccine activist, announced the names of eight new ACIP members in a post on X. At least two are well-known spreaders of vaccine misinformation, including one who is affiliated with an anti-vaccine group and believes her son was harmed by vaccines. Another has published dubious research suggesting COVID-19 vaccines are unsafe. Three have filed statements in court against vaccine manufacturers, including two who were paid to do so. An analysis by Science has also found that the new members, on average, have significantly less experience in vaccine science, as measured by publications, than the previous roster.

The new roster is set to participate in its first meeting on June 25.

Conflicts of Interest

Much of Kennedy’s justification for the removal of the sitting ACIP members rests on his contention that ACIP members have problematic conflicts of interest.

But as we’ve explained before, only those without significant conflicts are eligible, and panelists must file a financial disclosure report, update it annually and declare any conflicts at the beginning of each ACIP meeting.

According to the latest rules, updated in 2022, for example, neither ACIP members nor their immediate family members can be directly employed by a vaccine manufacturer. Members can only hold small amounts of stock in vaccine companies and cannot purchase stock while serving on the panel. Committee members also cannot hold a patent for a vaccine or be eligible for royalties for a vaccine that is expected to come before the panel, and generally cannot consult for or be paid for travel or speaking engagements by vaccine makers, among other requirements.

This does not mean that ACIP members cannot have any ties whatsoever to vaccine companies. Some experts test vaccines by running clinical trials or serve on the independent boards that monitor a trial’s progress and are compensated by vaccine manufacturers for their time. In these cases, an ACIP member would not be allowed to participate in discussions or vote on issues related to that vaccine. With a waiver, they would be able to discuss — but still not vote — on other vaccines made by the same company.

Dr. Sean O’Leary, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, told us that as someone who hasn’t worked on a clinical trial, he doesn’t always have the knowledge to ask the right questions when the companies are presenting their data to the committee.

“It is actually valuable to have people that have that expertise on the committee,” he said, adding that those individuals know where mistakes can be made and know how the safety data are collected.

As the policy itself notes, “it is critical that individuals chosen for membership on ACIP have significant vaccine and immunization expertise, including crosscutting knowledge and experience in the various aspects of the immunization field. Some expertise important to the committee can only be developed through working relationships with vaccine manufacturers.”

Dr. Kathryn Edwards, a Vanderbilt University vaccinologist who is now retired, told us that prohibiting scientists who have ever received any funding from pharma to study vaccines from serving on ACIP is “really seriously flawed,” since those individuals are the “most skilled” in evaluating vaccines.

In his Wall Street Journal editorial, Kennedy pointed to a 2009 HHS inspector general report to support his concerns about conflicts of interest. “Few committee members completed full conflict-of-interest forms—97% of them had omissions,” he said of the report’s findings. “The CDC took no significant action to remedy the omissions.”

The nearly 16-year-old report analyzed forms for 17 different CDC advisory committees — not just ACIP — for the single year of 2007. It found that the CDC had certified forms with at least one omission for 97% of individuals. But as an NPR investigation reported, the form is notoriously difficult to fill out, and the omissions are largely paperwork errors — not serious ethics violations.

According to the report’s Appendix D, for example, disclosures were often made but did not fully follow the form’s instructions, with items not listed in all the appropriate sections. Some information was only included on CVs or other included documents. In other cases, CDC reviewers did not date or initial changes.

For seven of the 246 individuals, or 3% of cases, members voted when they should not have. All of these cases occurred on the same, unnamed committee.

Contrary to Kennedy’s claim that the CDC took “no significant action,” a CDC response included at the end of the report, written by then-CDC Director Frieden, said the agency had already implemented changes. It also said that the inspector general report “failed to address the severity of the individual filings” and noted that the agency, for example, found it “impractical” to verify form items already included and “made obvious” on supplementary documents the CDC was already reviewing.

On two occasions since the publication of the editorial, Kennedy has gone even further, incorrectly claiming that the report, which he attributed to other groups, found that 97% of ACIP members had undisclosed conflicts or that 97% had conflicts of interest — a false claim he also made during his confirmation testimony.

“Congress said that 97% of the people on ACIP have had undisclosed conflicts,” Kennedy said in a press conference on June 10, misattributing the report. “People have known about this for years.”

O’Leary said Kennedy’s distortion of the 97% statistic is a classic case of him “cherry picking and manipulating data to suit his political agenda.”

Kennedy’s other main support for his conflict of interest claims comes from a 2000 House committee staff majority report. At the time, the committee was led by Indiana Republican Rep. Dan Burton, who pushed the incorrect notion that vaccines cause autism.

“Four out of eight ACIP members who voted in 1997 on guidelines for the Rotashield vaccine, subsequently withdrawn because of severe adverse events, had financial ties to pharmaceutical companies developing other rotavirus vaccines,” Kennedy said of the committee report in his Wall Street Journal editorial.

The majority staff report did say that of a June 1998 ACIP vote, and a Democratic congressman said in a hearing that his staff had identified the four individuals. But the ACIP rules at that time pertained to licensed vaccines, not those in development. According to the House hearing, it’s not clear whether each ACIP member even knew that the companies were working on a rotavirus vaccine. And as some critics have noted, if ACIP members were truly voting according to their financial interests, it’s not obvious that they would want to vote to recommend a competing product.

In other appearances, Kennedy has also recited this finding, although he has botched it, using the figure of four out of five. He has also incorrectly said Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and vaccine expert at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, voted to recommend RotaShield, but Offit told us he was not yet a member of ACIP.

Jason Schwartz, an associate professor at the Yale School of Public Health who has studied the history of ACIP, said that much of what Kennedy highlights is drawn from reports “that were 15, 20, 25 years ago, where admittedly those policies have evolved and strengthened, but don’t reflect today.”

Schwartz also said that the RotaShield example that Kennedy features is actually held up in public health circles as “a case study for how the vaccine safety system works — how it’s rigorous even after a vaccine is approved — and how these expert advisors responded quickly.”

The vaccine was approved and recommended in 1998. As we’ve explained before, in less than a year, the CDC identified in a vaccine safety monitoring system 10 reports of intussusception, a type of intestinal blockage, in infants who had received RotaShield. After further investigation, the agency temporarily suspended use of the vaccine, the manufacturer voluntarily recalled the vaccine, and ACIP withdrew its recommendation.

Although Kennedy suggests that the committee should have known not to recommend the vaccine in the first place, the serious side effect was so rare that it wasn’t clear there was an issue prior to a larger rollout.

“The signal did not emerge conclusively at the time the vaccine was approved and introduced,” Schwartz said, since not enough children had been vaccinated. Knowing of the potential risk, the Food and Drug Administration required that the trials for other rotavirus vaccines be significantly larger.

Kennedy also stated in his editorial that the conflicts of interest “persist.” But at the last ACIP meeting in April, most members had no conflicts to disclose; two members recused themselves from voting due to past participation in vaccine studies. And according to the CDC’s own online inventory of conflicts announced at each meeting from 2000 through 2024, which Kennedy’s HHS debuted on a website in March, only one person still serving on the committee had conflicts, again due to participation in trials.

Edwards, who is a former ACIP member and has also nominated people and written letters in support of ACIP applications, said the review process to add a new member, which can take a year or even longer, is “very rigorous.”

“There’s a lot of attention to conflicts,” she said, “and those have been thoroughly vetted.”

An investigation by Science of the 13 physician ACIP members Kennedy dismissed found “minimal” recent industry payments and “no sign” that members were compromised.

Edwards said the expelled ACIP members were “top-of-the-line … Cadillacs of vaccinology,” and noted that several did not have any current or past conflicts of any kind with vaccine makers, as they worked in public health. We asked HHS to state the problematic conflicts of interest for the dismissed panel, but did not receive a reply.

Rigorous Scrutiny of Vaccines

In his editorial, Kennedy stated that ACIP is “little more than a rubber stamp for any vaccine. It has never recommended against a vaccine—even those later withdrawn for safety reasons.”

Numerous experts, however, objected to this description.

“No, ‘rubber stamping’ is not a fair characterization and a comment that belittles the time, expertise and integrity of the members and their work. The ACIP has recommended against several vaccines, as a matter of fact,” Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, a public health researcher at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, told us.

Klausner had been working with Kennedy to identify new ACIP members, but told us he stopped at the end of March and was not involved in selecting the eight newly announced members.

“It is not true that ACIP is a rubber stamp, and not true that it was a rubber stamp when I was on ACIP back in 2007-11,” Dr. Janet A Englund, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Seattle Children’s Hospital, told us in an email, speaking in a personal capacity and not for her institution. “ACIP has often worked to limit or expand vaccine recommendations beyond that licensed by the FDA.”

Given concerns about effectiveness, ACIP said that in both the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 influenza seasons, the live attenuated flu vaccine, FluMist, should not be used. Due to successful immunization programs, ACIP also rescinded its routine smallpox vaccine recommendation in 1971 and removed its recommendation for a live polio vaccine in 1999.

Of course, the group also voted to remove its recommendation for RotaShield after safety issues came to light. As we said, there wasn’t sufficient evidence beforehand for the group to recommend against the vaccine.

In many other instances, usually after lengthy deliberations, the panel has decided to limit a vaccine to a particular population, or offer a more conditional recommendation that falls short of saying someone “should” get a vaccine, as it has done over the years with vaccines against pertussis, meningitis, HPV, RSV and Lyme disease, several experts told us.

Kennedy’s underlying premise is also misleading. ACIP does very often recommend vaccines because the vaccines have typically already undergone significant vetting by the FDA. The primary role of the committee is not to upvote or downvote the entire vaccine, but to advise on which groups of people should or could get the vaccine, based on which populations will benefit.

“It’s a really high bar to get a vaccine all the way through FDA licensure,” O’Leary said. “And so once that happens, that vaccine has already gone through a lot of hurdles. And so it is to be expected that most of the vaccines that FDA licenses would get some kind of a recommendation.”

Schwartz noted that ACIP has “remarkably rigorous, well-defined, formalized” processes that are transparent and show how the panel interpreted the available evidence to arrive at a decision.

“Folks might disagree with outcomes, but with respect to the process that informed their decision,” he said, “it was formal and rigorous and well structured.”

Staff Writer Kate Yandell contributed to this story.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.